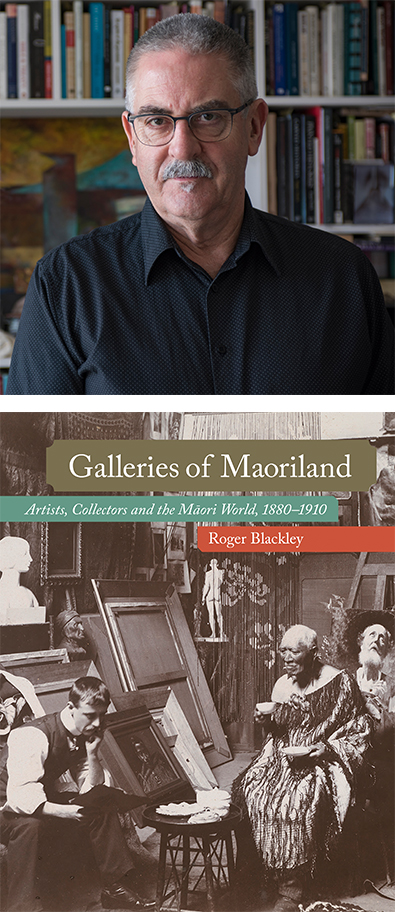

Literary critic and historian, Lydia Wevers, launched Roger Blackley's new book Galleries of Maoriland: Artists, Collectors and the Māori world, 1880–1910.

Most people here will have been in Roger’s office, that twilight zone where stacked books and journals loom towards the crepuscular semi-circle in which Roger is working, hoping that you are not the health and safety officer come to visit. I don’t think I have ever mentioned some art historical curiosity or factoid without Roger saying – I’ve got an article on that in one of my boxes. Like some of the people he writes about, and especially like William Gordon, the star of his book and exhibition Stray Leaves, Roger keeps everything. When Stray Leaves was published, its cover featured a gorgeous Trompe l’oeil painting by William Gordon of the surface of his desk, a self-portrait of letters, invitations, newspapers, magazines, cartes de visite. Someone, maybe it was me, suggested that Roger’s desk, or rather his room, would be a great author photo.

But what I want to focus on tonight is what comes out of Roger’s scholar-cave. It has been the scene of conception and the labour ward for the marvellous book we are here to celebrate tonight, Galleries of Maoriland Artists, Collectors and the Māori World, 1880–1910. Galleries has been gestating for the whole of Roger’s life. As he says in his preface, a question which struck me as truth as soon as I heard it – do we choose our fields of research or do they choose us? Roger dates his compulsive – well let’s not put too fine a point on it – obsessive, interest in ethnographic art, curios and the representation of Māori, to his childhood visits to the Māori hall in the Dominion Museum. His own life as a collector has taken him down the documentary route rather than the more grisly and barbaric paths chosen by some of his subjects, like Horatio Gordon Robley, notorious collector of Māori preserved heads. But since his book The Art of Alfred Sharpe, Roger has been preoccupied with the nineteenth century, a world teeming with artists and collectors, and coloured by their pictorial fascination with Māori subjects. Roger’s capacity to understand this world and bring it to life was shown in his magisterial exhibition of Goldie portraits at the Auckland Art Gallery in 1997 and the beautiful book which accompanied the show. If you look online you will find there are 14 files and 7 boxes of Roger Blackley’s curatorial notes, photos and correspondence in the Gallery archive, which seems modest. Goldie, Sharpe, Stray Leaves and Te Mata, Roger’s lovely 2010 exhibition and book for the Adam Art Gallery, on Nelson Illingworth’s Māori portrait busts, have all been stepping stones towards Galleries of Maoriland.

Galleries of Maoriland was already forming itself when Roger was persuaded he needed a PhD to be a proper academic. I think he likes being a doctor but the thing you can say about doing a PhD is that it forces a timeline on large and unwieldy topics. Roger’s examiners’ reports all recognised they were reading a remarkable piece of work and one that needed a wider audience than the three of them. As Tim Barringer put it, Galleries is a work of intellectual distinction. This is partly because Galleries of Maoriland challenges the prevailing binarisms of postcolonial readings of the nineteenth century and compellingly evokes a more complicated, messier, more intersecting world. But it is also becauseRoger’s decades of research into the many byways of the late-nineteenth century bring a level of detail to transactions and innovations that allows him to pose new questions, particularly about the role and motivations of Māori participants in the world of art and art collecting, evocatively suggested by the cover photograph of Patara Te Tuhi having a cup of tea while the young Charles Goldie looks glumly at a sketch. This is also a book which does not confine its interest or its definition of ‘art’ just to Lindauer portraits in gold frames. In Galleries art is transacted in studios, shop windows, outdoors, it encompasses curios, fakes, forgeries, loot, carving, painting, photography and performance. It is a vibrant and many dimensional account of greed, ambition, deception, pride, skill and affection. It is unflinching about the dark sides of the colonial encounter but doesn’t define everything on those terms.

Roger has been described as having encyclopaedic knowledge. I am not going to try to summarise this book – I couldn’t do such a task justice – but one of the things I love about it is how Roger delves into the murky underworlds of the nineteenth-century fever for ethnographic art, curios and antiquarian objects. Our museums and some of our private houses are filled with the loot that resulted from curio hunting, which became, as he says, a widespread leisure pastime. Roger describes curio hunters as people who crossed an important ethical line and became brazen tomb raiders, looting burial caves and urupa. Others made fun of human remains like the sons of prosperous Hawke’s Bay people described by Gilbert Mair: ‘one or two were Bank Clerks and one the son of a well known medical man in Hastings.’ Sarah Bernhardt, the ‘divine Sarah’, came in search of artefacts and, as Roger put it, ‘nonchalantly snapped up some of the greatest treasures ever unearthed in New Zealand’, spectacular and ancient Hauraki carvings, and turned them into panels on her sideboard. Walter Buller used his fluency in te reo Māori and deep familiarity with the Māori world to enrich himself at the expense of Māori land claimants.

The colonial encounter is always a paradigm of dispossession – Roger says it was a ‘massive transfer of Māori heritage material into the hands of the coloniser’. The book abounds with repugnant examples of racism, but it also documents the intellectual sophistication, cosmopolitanism and critical awareness of Māori people in characterising and condemning what was going on. As Maui Pomare poignantly described, ‘the stone axe has been loosened from its handle … the tattooed face is now an article of commodity …’

But some commodities have had a more mixed history. Although some Māori regarded photography and portraiture with deep suspicion, believing it captured and imprisoned the soul, anyone who has ever been to an exhibition opening of Goldie or Lindauer or Samuel Carnell’s photographic portraits has heard family members karanga and speak to their tīpuna. These European portraits are deeply held and living parts of te ao Māori. A Ngāti Kahungunu friend told me that when her house caught fire she rescued the Lindauer portrait of her great grandmother before she got the children out of the house.

Art history in New Zealand has tended to focus on categories of objects – painting, carving, photography – or on the histories of institutions or artists. Roger has mixed everything up, or rather, he has described the mixed up, inconsistent, various and colourful end-of-century world our ancestors actually lived in. Galleries of Maoriland is awash with people, objects, taonga and transactions – Patara Te Tuhi, King Tawhiao, Wi Tako, Renata Kawepo, Te Wherowhero, Te Whiti, the blithely ruthless Walter Buller, Augustus Hamilton, advocate for the preservation of taonga in museums, Johannes Andersen, first librarian of the Turnbull and prime cultural coloniser – it is Roger’s attempt to describe a whole world that is so compelling, and so successful.

I should disclose that I was one of Roger’s supervisors. My role was confined to reminding him when the little red engine was about to go off the track. Galleries of Maoriland emerged from the Aladdin’s cave that is Roger’s head, and the little engine can now head off to new fields of discovery.

Please join me in congratulating Roger.

Professor Lydia Wevers

Victoria University of Wellington

Image courtesy of Robert Cross Victoria University of Wellington