Five more AUP Poets reflect on 'The book that got me started ...'

Janis Freegard

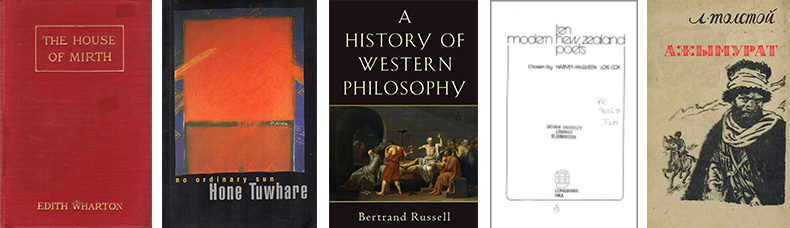

For Christmas 1977, my schoolfriend Jean (also a poet) gave me a copy of Ten Modern New Zealand Poets (eds Lois Cox & Harvey McQueen) which I’ll always be grateful for and which I’ve often returned to. I was already reading and writing poetry, but this was my first in-depth look at ten stellar New Zealand poets. Janet Frame’s spider of death, Bill Manhire’s blunt-fisted river and the defiant orange stickmen marching up Sam Hunt’s wall still travel with me. And I will spend the rest of my life trying to write something half as good as Kevin Ireland’s ‘Thorn and Wind’.

Lynn Jenner

Hadji Murat – Tolstoy’s last work. It opens with a Russian man walking through a field of pretty and modest wild flowers on an autumn day. A thistle with a scarlet flower catches his eye. In his efforts to pick the scarlet flower he hurts his hand and destroys the flower. The stalk of the thistle is left behind, bent and bruised but alive. A story of the Russian army in Chechnya in the 1850’s follows. Hadji Murat, a warlord who surrenders to the Russians, is brave and honourable and vain. The Russian generals are taking part in court politics thousands of miles away. The ordinary Russian soldiers suffer in ordinary ways. It could be the story of Russia in Afghanistan in the 1980’s or America in Afghanistan now. I like to imagine this as the last thing Tolstoy wanted to say.

Sam Sampson

On my 21st birthday I was given a copy of Bertrand Russell’s conspectus: A History of Western Philosophy. Much of it made no sense to me, like the rambling monologue of an erudite uncle ... but Russell somehow managed to hold my attention, peppering sections with a provocative mixture of humour, literature and social history.

There was a cast of characters – the virtuous and wicked – such as Pythagoras, who Russell described as a combination of Einstein and Mrs Eddy, whose Pythagorean order advocated abstaining from beans (and Russell’s conclusion: ‘but the unregenerate hankered after beans, and sooner or later rebelled’); and the resolute Nietzsche, debating with Buddha at the gates of heaven on whether beauty and goodness are nobler than cruelty and pain. ... It was soon after (reading Russell) I began my BA, majoring in Philosophy and favouring writers who constructed literature as a vehicle for their philosophic views.

Maybe it was this book? Maybe the eclectic mix of material from a multiplicity of texts led to my interest in poetry, and particularly, late-modernist poetry? Looking back (post-degree), the book seems overly long, and somewhat contrived, but it still remains a magnificent achievement. As Russell himself said: ‘I was sometimes accused by reviewers of writing not a true history but a biased account of the events that I arbitrarily chose to write of. But to my mind, a man without a bias cannot write interesting history – if, indeed, such man exists.’

Paula Green

Certain books have been like stones underfoot or adrenalin shots to the heart or brand new spectacles in my writing life but bookshelves got me started – not a single book. There was the bottom shelf at the public library with A A Milne poetry collections (and more!). There was the shelf above the bed at my great aunt and uncle’s with Jane Eyre, Middlemarch, Vanity Fair and other hardcover classics. There was the secondary-school library with a brand new copy of Hone Tuwhare’s No Ordinary Sun. There were endless novels on the shelves at Roy Parsons in my late teens; Doris Lessing, Herman Hesse, Mervyn Peake, Anais Nin, Simone de Beauvoir, Maurice Gee, Fiona Kidman, Richard Brautigan, Kurt Vonnegut, Marguerite Duras.

Harry Jones

Her name was half-known to me, and I’d often seen the spine in a second-hand bookshop. Edith Wharton conjured up dated shadows, and The House of Mirth was either light-headed or acerbic. Reading it matched any thrill in archaeology. Buried under layers of literary assumption, sunk by modernism, the prose remains a marvel of precise human perception and outstanding expertise in the language. From it emerged one of the most vital fictional figures I know, Lily Bart. She has led me to many other treasures of Wharton’s making, drawn out of a century of overlay and accretion, equally glittering, equally thrilling, equally real.