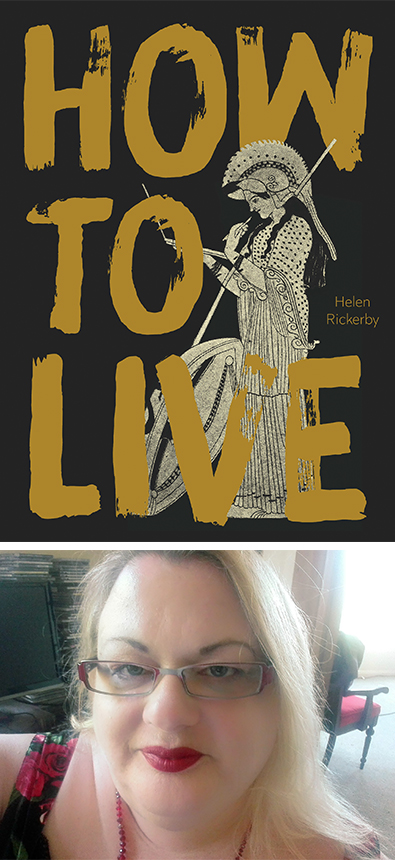

Helen Rickerby, author of new experimental poetry collection How to Live, considers woman writers, artists and thinkers from the past, and the obstacles in their way.

‘I think of all the books, paintings, music, scientific discoveries, philosophy I learned about in school – almost all by men. … And it strikes me: it’s not that women haven’t had the talent to make their mark in the world of ideas and art. They’ve never had the time.’ (Brigid Schulte)

In Brigid Schulte’s recent essay, ‘A woman’s greatest enemy? A lack of time to herself’,published recently on the Guardian website, she laments the lack of opportunity women have had to follow their own creative pursuits, or even get much time to themselves, throughout history and even still today. She tells stories of women who had talent, but lacked time, such as Gustave Mahler’s wife Alma, herself a promising composer – after they married he forbade her from composing and turned her into a support for his own talent. Theirs is perhaps a more pointed, deliberate, case, but many other women have been the ones to look after the children, the house, the family – jobs that aren’t just 9 to 5, but which never end – while the men in their lives are more able to cut adrift and follow their vocation.

Schulte points out that even today, when so many women are in the paid labour force, statistics show that women still spend a lot more time than men doing housework and childcare. Women’s time is valued differently, including by women themselves: ‘Feminist researchers have also found that many women don’t feel that they deserve long stretches of time to themselves, the way men do. They feel they have to earn it. And the only way to do that is to get to the end of a To Do list that never ends.’ Though this isn’t just a pressure we women are putting on ourselves – a recent study got people to look at photos of rooms and rate them for tidiness, and judged them more harshly if they were told the room belonged to a woman.

As important as it is, time isn’t the only factor that has held women back from their artistic or cultural pursuits – until fairly recently women of all classes were generally not given much of an education or training (and in some parts of the world that’s still true). They also lacked other opportunities, such as membership of professional organisations or general acceptance – there’s still a lot of bias, unconscious or otherwise, that women’s creations, or even thoughts, are not as good as men’s.

But, despite all of that, all the odds stacked against them, throughout history there have been women who have done amazing things. Some of them are relatively well known, like Joan of Arc or Mary Wollstonecraft, others are there if you look for them, and others will have been forgotten entirely. I have found that even women who were extremely successful and famous in their own time, such as English writer (and spy) Aphra Behn (1640–1689) or Italian painter Artemisia Gentileschi (1593–c. 1656), are often sidelined and forgotten by history. Many of Gentileschi’s paintings were, for example, erroneously attributed to her (much less talented, in my opinion) father Orazio.

Along with other woman artists and writers who have been rediscovered, particularly since second-wave feminism in the 1970s, Gentileschi’s reputation has been restored by researchers and scholars. Recovering women from the past matters for a lot of reasons, and one reason is because it gives women hope and pride. It is deflating to be told that there were no great women artists, or writers, or philosophers. If there have been none, then that must be because women are just not cut out for those pursuits. Better stay home, keep your house clean, your brain empty.

I have always been looking for women in history. I’ve had a series of fascinations with women writers, artists, historical figures – women who did stuff. And, as a poet, it’s not surprising that these women have found their way into my poetry. I’m really interested in how you can tell and explore a life in poetry. In a long, prose biography the emphasis is on information and making a story of the subject’s life, whereas biographical poetry (or verse biography, as it’s also known) tends to be more about moments, meaning and connections, using fragments and gaps and metaphor. Gentileschi is one of the women from history I wrote about in my second collection of poetry, My Iron Spine (2008), along with Emilies Brontë and Dickinson, Katherine Mansfield, Virginia Woolf and others. Exploring and retelling women’s lives is something I don’t seem to be able to stay away from, and have returned to in How to Live.

4. On her appearance

4.1. People go on and on about how ‘plain’ – by which they mean ugly – George Eliot was, including Mary Ann Evans herself, and every biographer since. But really, even though the remaining portraits might be flattering, they suggest that she was basically a fairly ordinary-looking woman with a slightly larger than average nose. I mean, her face might not have been fashionable at the time, but if she was walking past you down Lambton Quay, say, or Queen Street, you’d walk right past her without even a thought.

(From ‘George Eliot, A Life’)

The longest poem by far in How to Live is ‘George Eliot: A Life’, a prose poem in the form of a numbered technical report. I describe it as a deconstructed biography, because each section takes a different aspect of what you’d expect to find in a traditional biography and separates it from the chronological story. For example, there’s a section each on the different names she used, on her appearance, on some of the places she lived, on some of her most interesting friends and acquaintances – along with many digressions into my own thoughts and opinions. In ‘The Happiness of Mary Shelley’ I have another female novelist speak alongside two of her creations: Doctor Frankenstein and his ‘monster’. Both Eliot and Shelley are among the many female novelists who were extremely successful during their own lifetimes, and who also both lived very brave and unconventional lives.

There are advantages to widowhood, to being left behind. Men will only let women do ‘their’ work when there is no one else left. And she was the last one: her husband dead; her father, the venerable historian, dead; her brother, his successor, executed (he’d picked the wrong crowd, the losing side). And so it fell to her. She was summoned to court. She got her chance.

(From ‘Ban Zhao’)

When I was working on How to Live, I had a sudden, belated fascination with philosophy and philosophers. But I was really alarmed to find that I couldn’t think of many woman philosophers. There must be some, surely! And of course there were, but not very many. Perhaps of all pursuits philosophy is the one that needs the most of what women, and lower-class men for that matter, didn’t tend to have: time and education. But still, in the few books I found about women philosophers, I found stories of amazing women who did and thought and wrote amazing things. A couple of them have found their way into poems of their own. Ban Zhao (45–c. 116 AD) was a Chinese writer, philosopher and court librarian. Among the things she wrote was a treatise, Lessons for Women, which advocated equal education for women – something that has been a radical notion until quite recently.

8. I found her when I went looking for the philosophers who were also women. Where were they? You find them as soon as you look. Perhaps not many – few had the opportunity, the education, the space, and of the few, fewer are remembered. History has that way of erasing women – women are so forgettable – and of the few who are remembered, many are called something else: prophetess, wise woman, mystic, witch. Writer. We all know what a philosopher looks like: he has a beard, a robe, and carries a staff. We all know what a philosopher looks like: he has a serious look and two-day stubble above his turtleneck sweater.

(From ‘Notes on the Unsilent Woman’)

I was particularly struck by the story of Hipparchia (c. 350–c. 280 BC), an ancient Greek cynic philosopher who gave up her privileged life and wealth to become a poor philosopher with her husband Crates. At a time when respectable women basically stayed at home, this was also a way into a more public life. We know the little we know about her because of later writers, but all her own writings are lost to us. I was struck by the parallels in the way some of her contemporaries tried to shame her into silence, and the way people try to silence women now, especially on the internet – through questioning their femininity, and through threats of violence, especially sexual violence. My poem about her, ‘Notes on the Unsilent Woman’, took a long time to write – it started life as a one-page poem and ended up about two years later as 58 sections over 12 pages. While I was writing it, the #MeToo movement really got going, and there was a lot of talk about freedom of speech (which often seems to mean the freedom to denigrate other people) – things that seemed to me to be really relevant to the life of this exceptional woman from so long ago. Or maybe what I really mean is that the life of this exceptional woman from long ago is really relevant to us right now.

Some of the sections of ‘Notes in the Unsilent Woman’ simply list the names of pre-1900 women from different countries and cultures who, despite the many obstacles in their way, did find ways to achieve things: to make, to act. In incomplete roll call. The more you look, the more you find them there, being exceptional. But then I started wondering, if there are so many, maybe we should stop thinking of them as unusual, as unlike other women, as exceptions. Because there have always been amazing women doing amazing things despite the odds, despite the lack of time, despite the expectation that they’ll run the house, look after the children and be ladylike.

The same week I came across that essay by Schulze, I also read a review of a documentary that was supposed to be about a woman who inspired a man, but which was actually still all about the men in her life; an article about the side-lining of impressionist artist Berthe Morisot, and a piece about ‘the way women’s and men’s time is valued and the uneven burden taken by women writers in literary citizenship’ – i.e. ‘You get to be on one panel and be grateful, and make sure you support the male ego while you’re doing it.’ As these writers point out, we still have a long way to go in evening the playing field for women, both in terms of opportunities and recognition. We need few obstacles for women now, and more celebration of the women who have come before.